Thursday, 20 December 2018

The Road to Wigan Pier, by George Orwell

Thursday, 13 September 2018

The launch of Penguin Books

Saturday, 11 August 2018

Poets of the 1930s: what inspired them?

For the poets, there was much against which to protest, although the audience for their writings was always a limited one. Poetry had little to do with the mass media, and the works of Auden, MacNeice and Co, warning of disaster ahead, would only have had readers in their hundreds. It was only in the forties that a reasonably large poetry-reading public emerged, by which time the disasters had already occurred.

© John Welford

Tuesday, 26 June 2018

There Was An Old Woman Who Lived In a Shoe: what does it mean?

Monday, 7 May 2018

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead: a play by Tom Stoppard

Tom Stoppard took the title of his 1966 play from a line towards the end of Shakespeare’s “Hamlet”. All the main characters are dead, which leaves the concluding lines to be spoken by Hamlet’s friend Horatio and the Norwegian general Fortinbras. An ambassador from England announces that he has come too late to tell the Danish king that his orders have been obeyed and that “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are dead”.

Tuesday, 3 April 2018

Winnie-the-Pooh was Canadian

Thursday, 22 March 2018

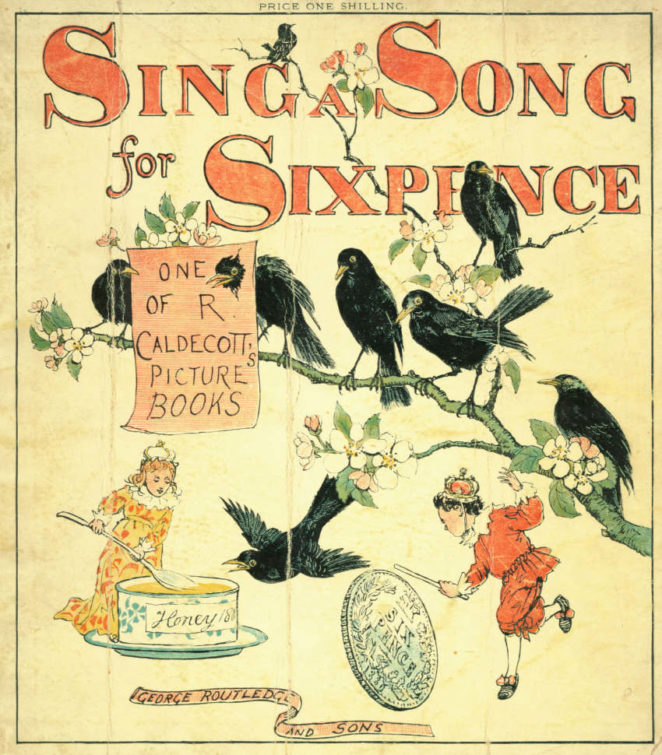

Sing a Song of Sixpence: a traditional nursery rhyme

Four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie

When the pie was opened the birds began to sing

Wasn’t that a dainty dish to set before the king?

The maid was in the garden, hanging out the clothes

When down came a blackbird and pecked off her nose

Nobody is completely sure about the origin of this rhyme, but it may have a similar root to that of “Little Jack Horner” in that both refer to items being hidden in pies. The latter rhyme is almost certainly a reference to an incident during the 16th century Dissolution of the Monasteries carried out on the orders of King Henry VIII, so it is entirely possible that “Sing a song of sixpence” has a similar theme.

King Henry ordered the break-up of England’s religious houses after he had declared himself to be the head of the English Church in opposition to the Pope. This came about after he had divorced his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, and married his second, Anne Boleyn, who was fated to fall from grace even more spectacularly. Neither queen had been able to provide Henry with what he most desired, namely a male heir.

So that accounts for the king, the queen (Catherine) and the maid (Anne). In “Little Jack Horner” the pie contained the deeds of monastic houses that were being conveyed to the king, so the blackbirds could easily be the same, or black-clad protestant clergymen who were only too happy to seize the deeds and present them to the king, in the expectation of rewards and preferments coming their way. On arrival, much “singing” would take place and the king would have plenty of “sixpences” to count in his counting house.

However, one particular blackbird, namely Thomas Cromwell who was King Henry’s Machiavellian chief minister, would later play a decisive role in the fall of Ann Boleyn who would lose considerably more than just her nose.

© John Welford

Wednesday, 21 March 2018

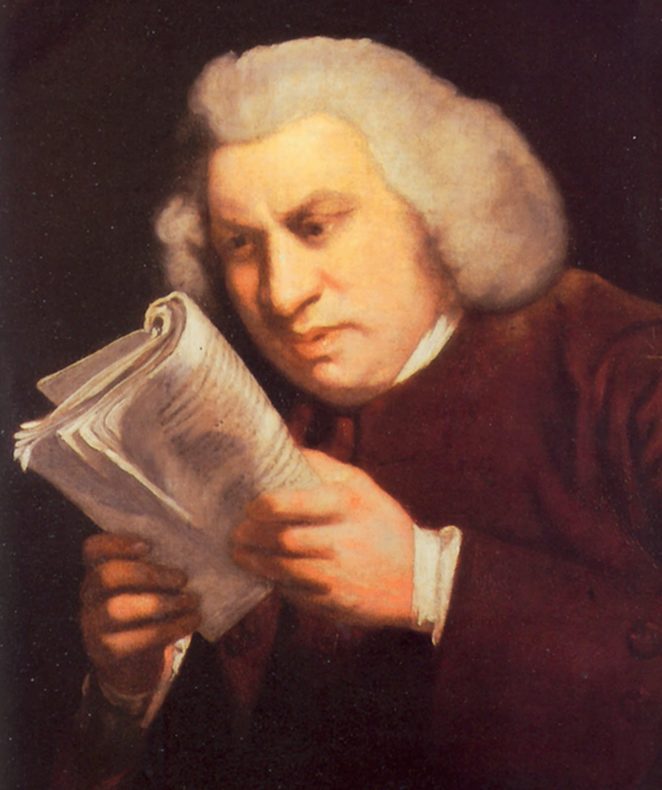

Rasselas, by Samuel Johnson

Pussy Cat, Pussy Cat, Where Have You Been? A traditional nursery rhyme

I’ve been to London to look at the Queen.

Pussy cat, pussy cat, what did you there?

I frightened a little mouse under her chair.

As the cat slept on, the Queen arrived, as did her courtiers and the dignitaries, possibly foreign ambassadors, who had been granted an audience.

Monday, 19 March 2018

Jack Sprat: a traditional nursery rhyme

Jack Sprat could eat no fat

His wife could eat no lean

And so between them both

They licked the platter clean

This familiar nursery rhyme may have its origin back in the 12th century when King Richard I set off on a crusade and left the realm of England in the care of his younger brother Prince John. John was the youngest of four sons, and thus the runt of the litter – or “Jack Sprat”.

John’s wife, Isabella of Gloucester, was renowned for her

personal greed. She had, after all, gained all the property belonging to the

earldom of Gloucester after her two sisters were disinherited in her favour by

her marriage agreement to John.

However, the action mentioned in the rhyme probably had a more laudable motive than might appear at first sight. When Richard was on his way home from the crusade he was captured by Duke Leopold of Austria, who handed him over to the Holy Roman Emperor who in turn demanded a massive ransom for his release.

John and Isabella then set about gathering the money by all

means available. They exhausted their own funds and then set about getting as

much as they could from the rest of England, including raising taxes on clergy

and laymen to the value of a quarter of their property.

They thus “licked the platter clean” in their efforts to

bring Richard home, which were eventually successful. John’s subsequent

unpopularity stemmed in part from this attempt to support his more popular

brother, despite the fact that Richard only spent a few months of his ten year

reign in England.

I Had a Little Nut Tree: the meaning behind a traditional nursery rhyme

The rhyme

Nothing would it bear

But a silver nutmeg

And a golden pear.

Came to visit me,

And all for sake

Of my little nut tree.

Jet black was her hair,

She asked me for my nut tree

And my golden pear.

Never did I see;

I will give you all the fruit

From my little nut tree.”

© John Welford