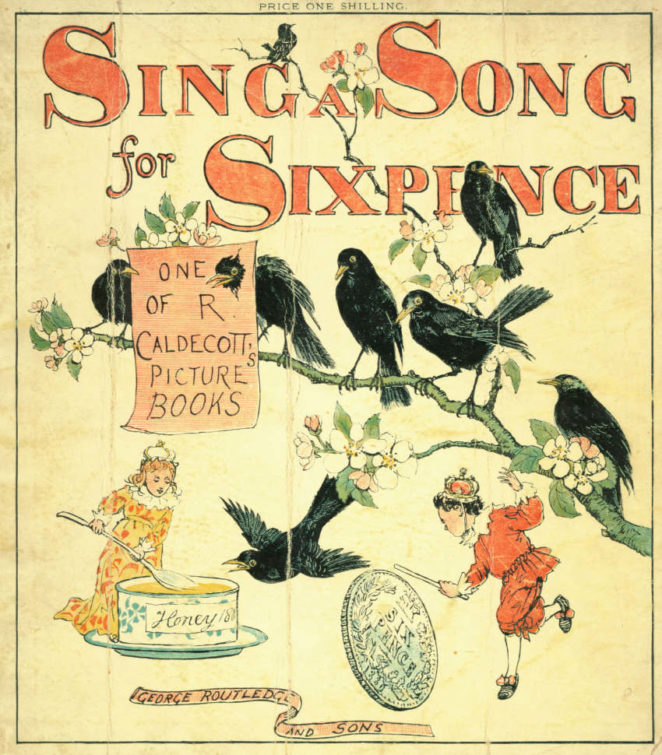

Four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie

When the pie was opened the birds began to sing

Wasn’t that a dainty dish to set before the king?

The maid was in the garden, hanging out the clothes

When down came a blackbird and pecked off her nose

Nobody is completely sure about the origin of this rhyme, but it may have a similar root to that of “Little Jack Horner” in that both refer to items being hidden in pies. The latter rhyme is almost certainly a reference to an incident during the 16th century Dissolution of the Monasteries carried out on the orders of King Henry VIII, so it is entirely possible that “Sing a song of sixpence” has a similar theme.

King Henry ordered the break-up of England’s religious houses after he had declared himself to be the head of the English Church in opposition to the Pope. This came about after he had divorced his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, and married his second, Anne Boleyn, who was fated to fall from grace even more spectacularly. Neither queen had been able to provide Henry with what he most desired, namely a male heir.

So that accounts for the king, the queen (Catherine) and the maid (Anne). In “Little Jack Horner” the pie contained the deeds of monastic houses that were being conveyed to the king, so the blackbirds could easily be the same, or black-clad protestant clergymen who were only too happy to seize the deeds and present them to the king, in the expectation of rewards and preferments coming their way. On arrival, much “singing” would take place and the king would have plenty of “sixpences” to count in his counting house.

However, one particular blackbird, namely Thomas Cromwell who was King Henry’s Machiavellian chief minister, would later play a decisive role in the fall of Ann Boleyn who would lose considerably more than just her nose.

© John Welford